Were Animals In The Middle Ages Viewed Differently Than Today

Content and Spoiler Warning: The below commodity contains both spoilers for Flavor 5, Episode half dozen of Game of Thrones equally well as frank discussions of rape and sexual violence.

Editor'south Notation: This article is significantly longer than usual for The Public Medievalist. I did this because the topic is a very hard i, and there are a lot of issues explored here that demand a longer class to even scratch the surface. Thank you also to Amy Kaufmann for reviewing this article and offering very helpful suggestions for revision.

Equally a medievalist interested in popular culture, I've been asked past a handful of people to comment on that scene from a recent episode of Game of Thrones (season 5, episode 6). If you lot saw it, you probably know which ane I mean: Sansa Stark is married to Ramsay Bolton—the currently-reigning Worst Person in Westeros (a title ever under fierce competition). Predictably—and horribly—he then rapes her on their nuptials night. At this point in the show, Sansa is many things, but not so naive as she started out. It is heavily implied that she knew what she was getting herself into, but accustomed this fate so that she can become closer to the targets of her vengeance. That doesn't make it any less horrible though—and obviously does non in any mode equal consent.

Since its airing, there has been considerable give-and-take on the net about that scene; some defendant it of being "complimentary." Because that the show is one of the near popular depictions of the medievalesque in recent years, depicting marital rape in the prove this raises a number of questions almost the realities of sexual violence in medieval Europe.

Our Game of Thrones Middle Ages

As a brief side-note, there are roughly two reigning versions of the Centre Ages in the popular imagination—one low-cal, bright and merry, the other dark, muddy and bloody. The light and merry vision has been on the refuse in film and Boob tube since the 1970s (with a few notable exceptions), replaced by a more "developed," ostensibly "realistic" depiction of the medieval world as one populated by barbaric people exacting atrocities upon ane another under a darkened sky. Game of Thrones is currently the ne plus ultra of this subgenre.

Depicting the Middle Ages equally bloody and brutal serves a purpose in our collective memories. We are conditioned to see ourselves as participating in a supposedly-enlightened post-modern age. The structural narratives of our age promote the idea of progress—which is as obvious in our technology as in our social ideals. Women achieved the right to vote a hundred years ago, the ceremonious rights move is turning 50, the gay rights motility has achieved successes at a charge per unit that baffles even the justices of the supreme court. Our rights are getting righter—and our wrongs are beingness shoved into the by.

This makes the origin of our club—the medieval earth—logically the worst of all possible places; the very nadir of western gild (any that is): "The Nighttime Ages". It is little wonder that the two crimes that are, arguably, worse than decease—rape and torture—are understood to have been common features of the historic period (though they're not, but that'south some other article). It is such a expert thing that nosotros never practice those any more, and instead are kept safely at arm'southward length past being ascribed to our imaginary Heart Ages. To Ramsay Bolton.

Uncomfortable Answers to Uncomfortable Questions

Allow me be clear: I am not maxim that rape did non happen in the Center Ages. What I am saying is that it has been one of the great horrifying constants in our society throughout every age, and that in many ways we are non so far from our medieval forebears in our perception of it. One of the questions that follows from this is not whether rape occurred, but how common it was, how acceptable it was seen to be, and whether a hypothetical medieval person watching Game of Thrones would react in the same way we practice. Was Sansa's story normal? Did every bride in the Heart Ages expect she was consigned to a life of being raped by her hubby? Or was this the exception to the rule?

A principal problem in examining the problem of rape in the Eye Ages is the same problem you encounter when trying to study anything relating to the lives of women: that is, the sources. For our purposes, and without getting too far into the weeds, the best sources nosotros have on the question of rape and whether it was acceptable are the Church doctrines and laws nearly matrimony, the court records, diaries and literature. The problem is that most were written past men in positions of ability—the voices of women, and the stories of the non-aristocratic—prove difficult to notice.

The Church building and "Traditional Marriage"

As a medievalist, I am frequently amused by the yawning gulf between what contemporary conservatives call "traditional marriage" that has supposedly existed unchanged for "millennia," and the realities of marriage as it existed in the Middle Ages. What most of these conservatives don't recognize is that the establishment of marriage has e'er been under negotiation and interpretation. In the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, the Church fought tooth and nail to bring marriage—which had previously largely been a secular contract between families—under their exclusive control. Role of this involved intense negotiations among the clergy nigh sexuality: what should and shouldn't be forbidden, what is expected of both parties in a spousal relationship, and whether sexual practice is required for a spousal relationship to exist valid (they eventually decided that it is).

I touchstone for the church is in Corinthians, where the Apostle Paul set a surprisingly (for him) even-handed standard:

The married man should fulfill his marital duty to his wife, and too the married woman to her husband. The wife does non have authority over her own body but yields it to her husband. In the same way, the husband does non have authority over his ain body simply yields it to his wife. ( 1 Cor., vii:3-4 )

From this, medieval church lawyers developed the "doctrine of bridal debt". On the surface, this seems to set a skilful precedent; within a spousal relationship or long-term romantic partnership, being committed to meeting your partner's sexual needs (as function of a general obligation to their emotional and physical wellbeing) is not necessarily a bad ideal to live by.Chaucer'south Wife of Bath famously refers to this doctrine when she demands sex from her husbands:

Why else should men into their ledgers gear up

That every human yield to his wife her debt?

And how can he pay this emolument

Unless he utilize his simple instrument?

Hurr hurr.

Past contemporary feminist standards however, Paul goes mode too far. It's piece of cake to see how beingness forced to requite upward autonomy over your body could be a huge problem—especially when society treats women, consistently, as belongings.

Marriage among the Medieval Elite

Further complicating the issue is the fact that marriage was often not voluntary in the Middle Ages. Part of the fight over union (wherein the church asserted its authority over information technology) in the high-middle ages was almost the idea of consent; prior to this, it was quite common for a person to exist married to someone without their consent or even noesis—simply bundled and sealed without any consultation. The church seems to take gotten that one correct, at least.

Well-nigh people are familiar with the thought that people at that time were married very young, and that arranged marriages were the norm. I'm happy to report that this was not always the case; prepubescent betrothals were typical only for those amidst the aristocracy who had a express puddle of peers. Equally you move up the social pyramid, in that location are fewer and fewer people around your particular rung, which means practiced matches for your sons and daughters (meaning ones that increment your wealth or social continuing) become a chip thin on the ground. That is certainly not to say that marriages were not arranged; they very ofttimes were. For example the History of the Counts of Guines provides a classic case of aristocratic marriages, where the eldest men of the family (often grandfathers or fathers, but sometimes uncles or even older siblings) would adjust marriages for the women in the family in guild to increase their own prospects and that of their clan. Sons sometimes could notice their ain bride, only not e'er—and frequently only with blessing from the patriarch.

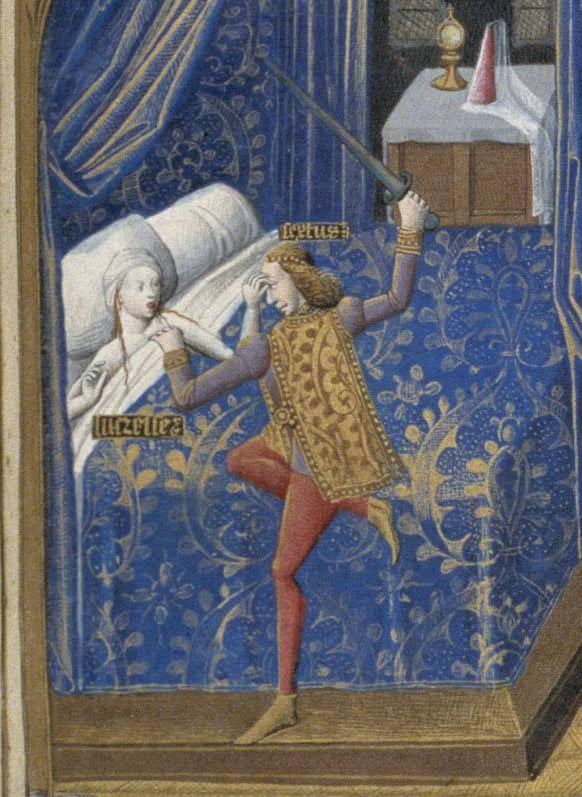

If that were not bad plenty for aristocratic women, there was another option for the aggressive bachelor: spousal relationship past abduction. Yes, it was considered a valid part of "traditional matrimony" during much of the Middle Ages for a man to acquire a helpmate by kidnapping an eligible adult female and forcing her to ally him. And since, as discussed above, a marriage is not fully binding until sex, in that location is the implication that rape was necessarily part of this. This is non limited to thuggish fiddling knights roaming the countryside; both Theobald V, Count of Blois, and Geoffrey, Count of Nantes attempted to ally Eleanor of Aquitaine—then the about eligible adult female in Europe—past kidnapping her. Cleverly, Eleanor managed to evade them, and afterwards elected to get married very chop-chop, not to the lowest degree to thwart these and whatever future plots. But what a truly horrid choice to be forced into—being required to exist married out of fear that you volition be kidnapped, raped and forced to marry your rapist. Making matters even worse, as Caroline Dunn argues, that lawmakers typically "neglected unwilling victims of bride-theft because their focus was on consensual elopements." In other words, they were as well decorated cracking down on couples eloping against the wishes of their aristocratic families than on the women kidnapped confronting their will.

Union For Everybody Else

Outside of the machinations of the elite, in that location is little reason to believe that for those in the vast unlanded majority that the world operated in quite this fashion. It is impossible to know without evidence what the typical model for matrimony amongst the working majority was. But, with fewer considerations of land and dynasty—and a rather-larger puddle of potential mates—the organization may not take been quite and then strict as for the aristocracy. But that does not at all mean that life was meliorate for women of the lower classes.

Accept equally a case in point one of the major works discussing love and sex during the Eye Ages, On Honey by Andreas Capellanus from the 12th century. In that location is some contend over whether Capellanus was writing satire(information technology may be a rehash of Ovid'southward Ars Amorata which was itself something of a satire), but in my stance, he was not. He spends huge swathes of his text amalgam a how-to guide for the lover ("dearest" here existence roughly interchangeable with sex)—especially for his aristocratic male audience in seducing a lover of an appropriate social rank. His work crystallizes the ideal of the obsessive, "chivalric" lover that so entranced the readers of the nineteenth century—but that is the topic of another article.

When information technology comes to loving peasants, however, Capellanus has entirely different advice. Peasants are not capable of true loving, according to him, but copulate like beasts. If you wish to engage in loving with a peasant, he offers this communication:

Be careful to puff her up with lots of praise and and so, when yous discover a convenient place, do not hesitate to take what you seek and to embrace her by force. For you can inappreciably soften their outward inflexibility and so far that they volition grant you their embrace quietly or permit yous to accept the solaces you desire unless kickoff you use a little compulsion every bit a convenient cure for their shyness.

The law of Jus Primae Noctis–where the lord had the right to sex with any peasant bride on his lands on her wedding night—is entirely made up (no thing what Braveheart depicts). Merely if Capellanus' words are reflective of reality, then things were rather worse. The rich and powerful, it seems, were encouraged simply to accept whoever they wanted by force, with picayune repercussions.

Rampant Medieval Ladyboners

Making matters perhaps worse, there was a fundamentally unlike popular perception of female desire than at that place is today. Whereas today there is a common perception that men are hornier–they "only have ane affair on their mind" or "think almost sexual practice every 7 seconds" (both of which are demonstrably simulated, of course), during the Heart Ages it was widely understood that women were more libidinous than men. Medieval thinkers were highly influenced by Ovid on the topic; Angeliki Laiou refers to a number of peculiar metaphors medieval thinkers came to when describing their theory:

The estrus of female person desire resembles wet wood, which catches fire less readily but burns longer and more than strongly… The composition of the female uterus is more like iron which warms slowly but holds its oestrus longer… Female person desire is like burning coals covered with ashes. They burn with greater heat, intensity, and duration than the more than open passions of men.

But as is so often the instance, women are caught past this image; their allegedly "hotter" nature is yet some other manifestation of their inherent sinfulness—the inheritors of Eve'south folly. In more than prosaic terms, it is easy to see how this reading of female sexuality would perpetuate medieval rape civilization. Like Capellanus said of peasants—they always want it, they only demand provocation. As a result, even women who were raped were judged harshly past society since the mutual agreement was that they were at least partly responsible. Thus equally Margaret Schaus argues, "many rape survivors were unable to notice a wedlock partner and swelled the ranks of prostitutes."

That's not to say that rape was not considered a crime during the Middle Ages. Information technology was—especially when a woman's virginity was violated. But, it was a crime that does not seem to be taken seriously unless the woman was rich and powerful. This is because the crime was considered to take perpetrated not just against the woman herself just confronting her entire family—her sexual purity beingness a valuable article on the marriage market, having that taken by someone was considered a serious crime.

Sansa'due south Plight, and Ours

So, in essence, rape was considered a prosecutable criminal offence in the Middle Ages, just in a very limited fashion. Like with so many things, unless yous had a powerful family and non however married, the woman was either considered to have been partially (or wholly) responsible, it was not considered a serious law-breaking or, if she were married, no crime at all.

So, where does that leave poor Sansa—and by extension all medieval women? Would all go to their wedding beds with the expectation of being raped—or that their consent was an optional accessory rather than required? Plainly, that depends. People in every age have conformed to or pushed confronting the norms of their day, and historical records (e.g. court records, etc.) privilege when things go incorrect. Merely considering the prevailing winds at the time, for a woman to discover they were being married to a partner who treated them with respect and kindness might have been more than of a pleasant surprise than an expected outcome.

I am reminded of the song "Matchmaker" from Fiddler on the Roof, where three young women limited their hopes and fears well-nigh existence married off by their begetter:

Chava, I found him.

Won't you be a lucky helpmate!

He's handsome, he'southward tall,

That is from side to side.Just he's a nice homo, a good catch, right?

Right.You heard he has a temper.

He'll beat you every nighttime,

Simply only when he's sober,

So you're alright.Did y'all think you'd get a prince?

Well I do the all-time I can.

With no dowry, no money, no family groundwork

Be glad you got a human!

But on the other hand, this raises a conundrum: to what caste does civilisation shape people, or practice people shape culture? I discover information technology difficult to accept that simply because jurists or clerics said that marital rape was fine, (and aristocratic systems practically encouraged information technology) and that some poets encouraged the rape of peasants, that it means that all, or even most, men were rapists. It does mean those already inclined to exist trigger-happy and sociopathic—like the Ramsays of the medieval world—would get away with it (and possibly fifty-fifty be encouraged). Many might exist persuadable, in the same manner that warrior-groups (whether gangs or armies) often encouraged vehement behavior among their members. Merely it does non hateful that kindness and empathy ceased to exist, and that at that place were non people who did non "fit in" with the prevailing winds of their society.

Non all medieval men were Ramsay Bolton—though it seems equally though their society encouraged them to conduct more like Ramsay than like Tyrion. Many of the social norms described higher up are abhorrent. But it is of import non to ignore medieval men'southward bones humanity when trying to recuperate the basic humanity of medieval women.

And permit's not get as well smug when reveling in the supposed barbarity of our medieval forebears. Marital rape was only criminalized in all 50 states in the USA in 1993—and only as a effect of the concerted effort of feminists for almost 150 years. Though figures vary, at a bourgeois estimate one in six women in the U.s. today have either been raped or are the victim of an attempted rape. And the rich and powerful nonetheless often get away with it. Women are still abducted and raped into wedlock. Aye, rape culture in the medieval west was horrifying, but if the ideas explored above—that women are "asking for it," or secretly "desire it," that women who are raped are considered "damaged goods," or that husbands have "the correct" to their wives' bodies—if you've never heard those ideas, then y'all oasis't been paying plenty attention. Nosotros still accept a long mode nonetheless to go.

Click Hither to donate to RAINN (Rape, Corruption and Incest National Network) the largest anti-sexual violence organization in the US. They practice good work.

Source: https://www.publicmedievalist.com/got-rape-and-middle-ages/

Posted by: johnsonshouseedee.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Were Animals In The Middle Ages Viewed Differently Than Today"

Post a Comment